Upstate New York Trip Part 3 — Niagara Falls

(Translated from the Chinese version with the help of ChatGPT.)

At last, we arrived at the final stop of this trip — Niagara Falls.

Other posts in this series:

Early in the morning, we drove from our hotel toward the Falls. Several kilometers away, we could already see a massive column of mist spiraling upward from the direction of the falls, accompanied by the faint roar of water — the atmosphere was perfectly set. We arrived around 10 a.m. Though it was a weekend, we were still early enough to find a few empty spots in Parking Lot 1 (P1 on the map), closest to the Visitor Center.

The parking lot lamps greet visitors in multiple languages, including Chinese — a heartwarming touch.

Niagara Falls State Park map

Note that the top of the map points west. Across the river lies Canada. Yes — at this spot, Canada is actually west of the U.S. (Fun fact: near Detroit, there’s a section of the border where Canada is south of the U.S.!) Both cities on either side of the river are named Niagara Falls — distinguished by “NY” and “Ontario.” The Niagara River flows roughly east to west, splits around Goat Island (the green island on the left of the map), plunges over the cliffs to form the falls, then turns north. The border runs down the middle of the river. The Horseshoe Falls (on the left) belongs to Canada and carries about 90% of the river’s water. Goat Island and the American Falls on the right belong to the U.S. Near Goat Island is tiny Luna Island (Point 4), separating the Bridal Veil Falls — the smallest of the three.

Riding the Maid of the Mist — Up Close with the Falls

We headed straight for the Observation Tower after parking. Along the way, there’s a ticket booth for the boat ride. We had already purchased vouchers online and just needed to exchange them, but the line wasn’t long — you could easily buy tickets on-site. (A quick rant: the official website maidofthemist.com has poor browser compatibility. Firefox froze during payment, but Chrome and Safari worked fine.)

From the Observation Tower, I realized we were actually above the falls. To board the boat, we had to take the elevator down to the river level (Point 8 on the map).

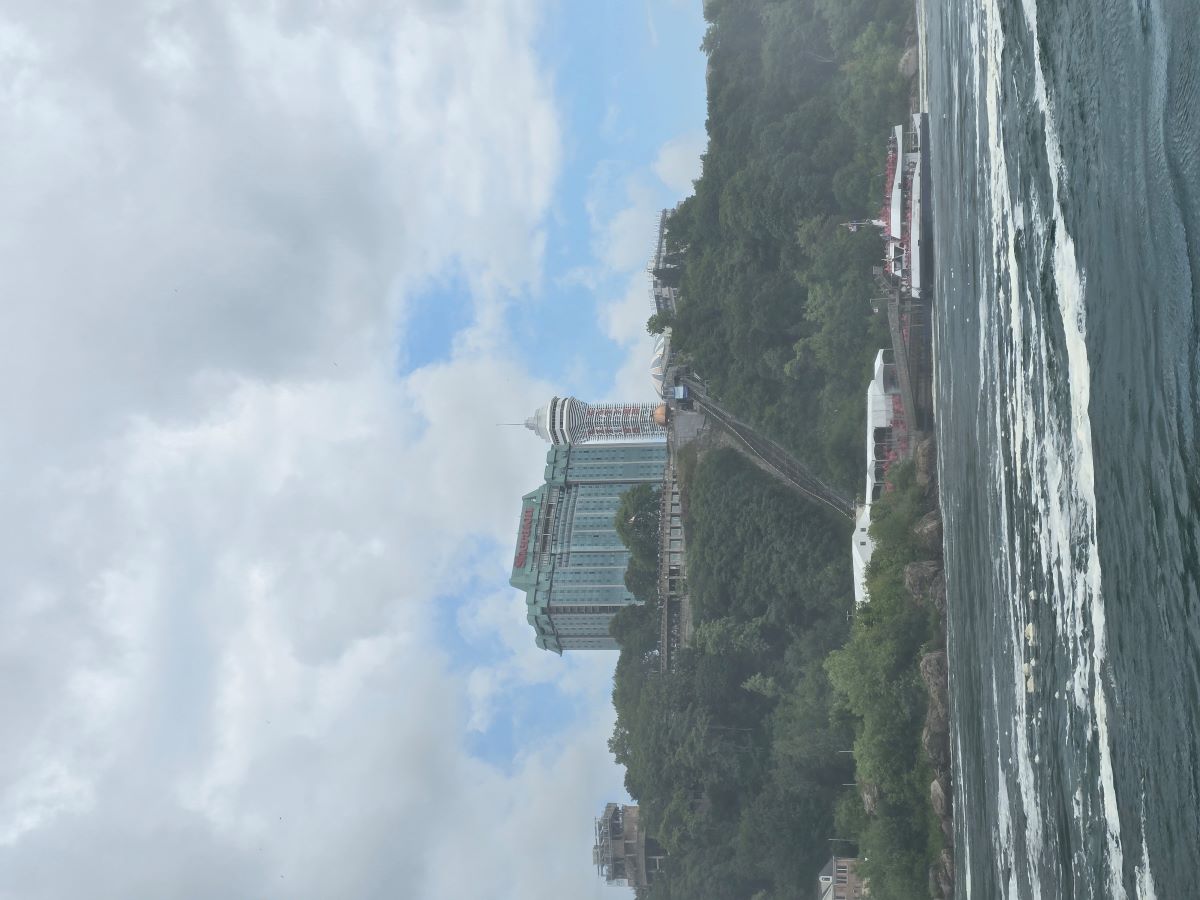

View of the Observation Tower from the river — quite a drop!

Across the river, the Canadian side has a similar setup with a funicular going down to the dock. Their ponchos are red; ours are blue.

Down at the riverbank, there was no line — we were handed blue ponchos and boarded right away. We took the crew’s advice and stood at the front of the lower deck. Engines rumbled, and off we went!

First up, the American Falls — about 10% of the river’s flow, 250 meters wide and 57 meters tall.

Next, the tiny Bridal Veil Falls, only 17 meters wide. People in yellow ponchos can be seen walking the 'Cave of the Winds' boardwalk below.

Then came the main event — the mighty Horseshoe Falls. Nearly 790 meters wide, carrying 90% of the Niagara River’s flow — enough to fill 15,000 bathtubs every second! 🤯 The mist soaked our faces; I can barely see anything through my glasses. The thunderous 270-degree wall of water surrounded us completely. Overwhelmed by its power, I couldn’t help but shout in awe.

Looking back, I noticed most passengers had retreated inside, leaving only a few of us — better prepared and unafraid of getting drenched — still standing proudly at the bow. After what felt like ten minutes facing the falls, the boat finally turned back.

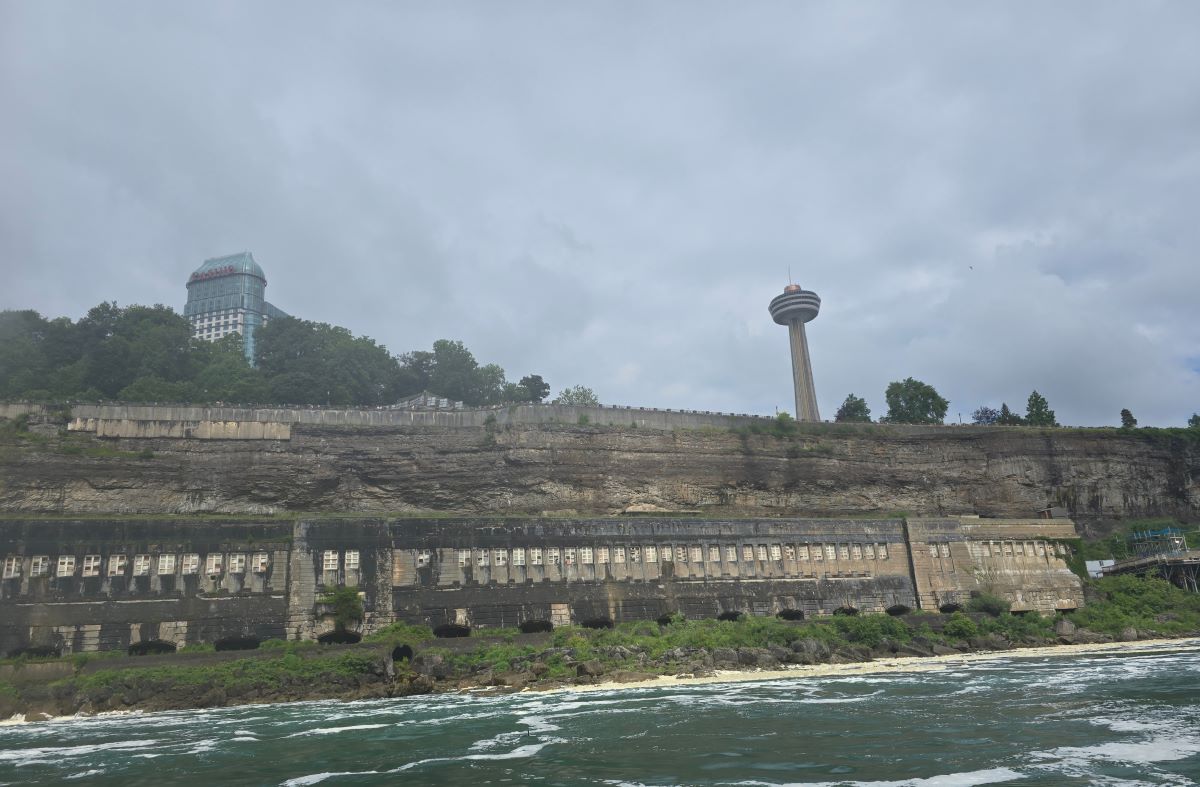

Abandoned building on the Canadian cliff — once part of an old power plant?

After docking, the crew plugged in the boat. These electric vessels were introduced in 2020.

Back on Top of the Falls

We took the elevator back up to the Observation Tower. The sun had come out — perfect for more sightseeing and drying off a bit before moving on.

Looking south toward the falls from the Observation Tower.

Looking north toward the Rainbow Bridge (Point 10 on the map), connecting the U.S. and Canada.

From Luna Island (Point 4), you can see both the Bridal Veil and American Falls, as well as tourists at the Cave of the Winds1.

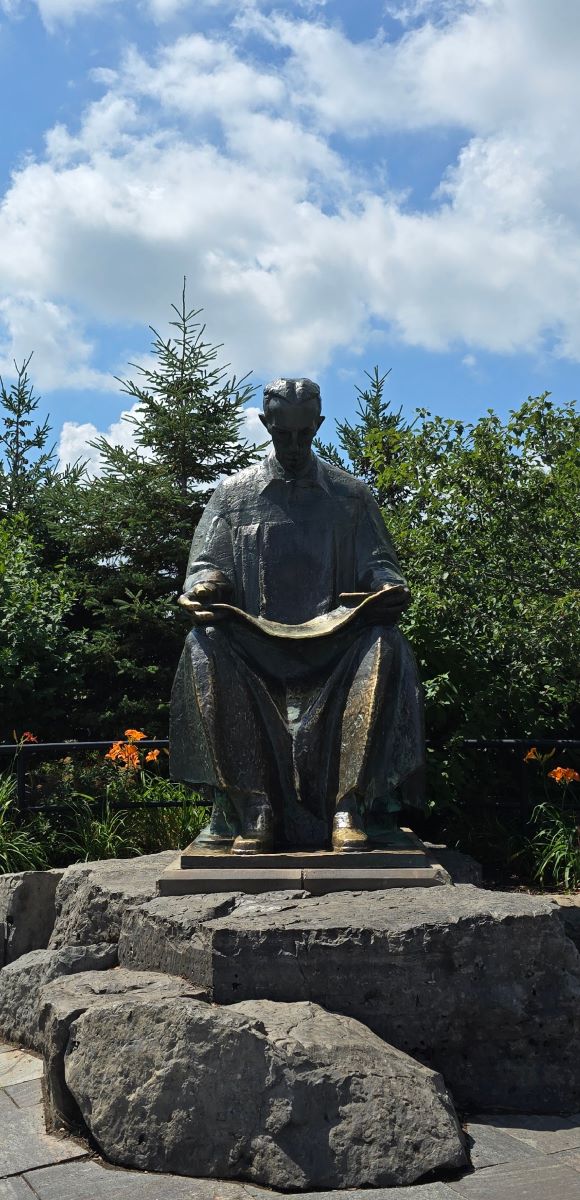

Continuing toward Terrapin Point (Point 2), we first encountered a statue of Nikola Tesla.

Statue of Nikola Tesla

In 1884, a 28-year-old Tesla immigrated to the United States and later joined George Westinghouse’s company. Together, they built a hydroelectric power station here. On November 15, 1896, they achieved the first long-distance transmission of alternating current — from Niagara Falls to Buffalo, 23 miles away. Writing this post on my desktop computer today, I can only feel deep respect and gratitude to those pioneers.

Then I spotted a familiar red, white, and blue historical marker — could it be the Marquis de Lafayette again? This was my third unexpected “meeting” with him after Hartford and West Point. The sign noted that Lafayette was an abolitionist and human rights advocate — as early as 1783, he called for the abolition of slavery, challenging even Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. Many abolitionists came to Niagara Falls, as it was a key stop on the Underground Railroad; countless freedom seekers crossed here into Canada.

Marquis de Lafayette visited Goat Island on June 5, 1825.

Here’s the official video retracing Lafayette’s 1825 visit to Niagara Falls:

At Terrapin Point, you get a side view of the Horseshoe Falls:

Schoellkopf Power Station Ruins

By now, we had seen most of the major attractions. It was still just past noon, so after lunch, we decided to check out the Schoellkopf Power Station ruins (Point 11 on the map)2. It was nearly a half-hour walk3 before we reached a building by the cliff.

Entrance to the Schoellkopf Power Station ruins

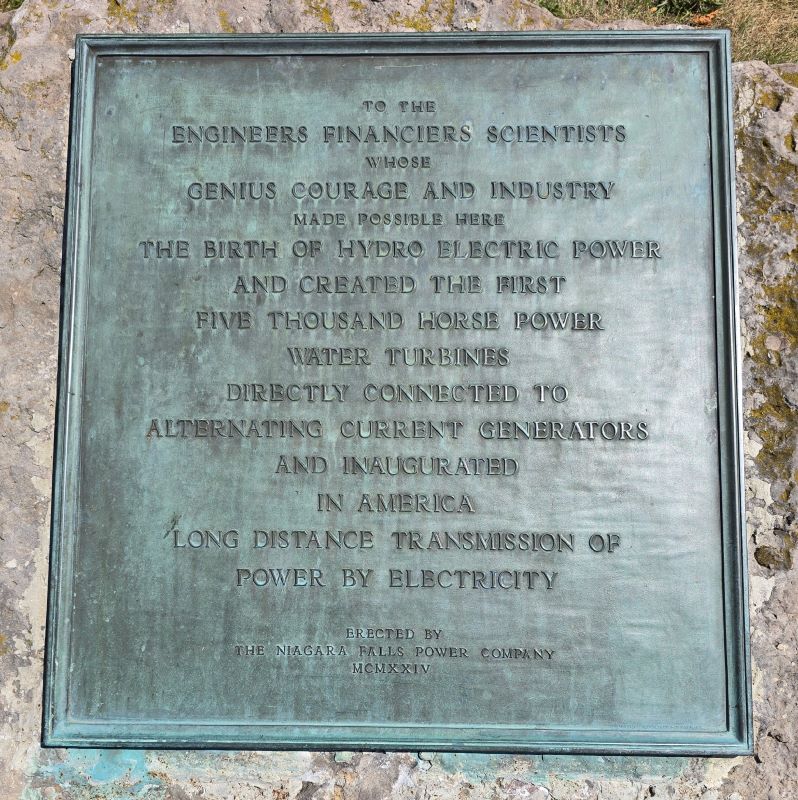

A 1924 memorial stone honoring the engineers, financiers, and scientists behind the Niagara Falls Power Company.

Inside, an elevator took us back down to river level. Turning around, we could see the elevator shaft built right into the cliff.

The elevator shaft wall

Next to it, part of the cliff was missing —

Something terrible happened here.

An exhibit explained the tragedy.

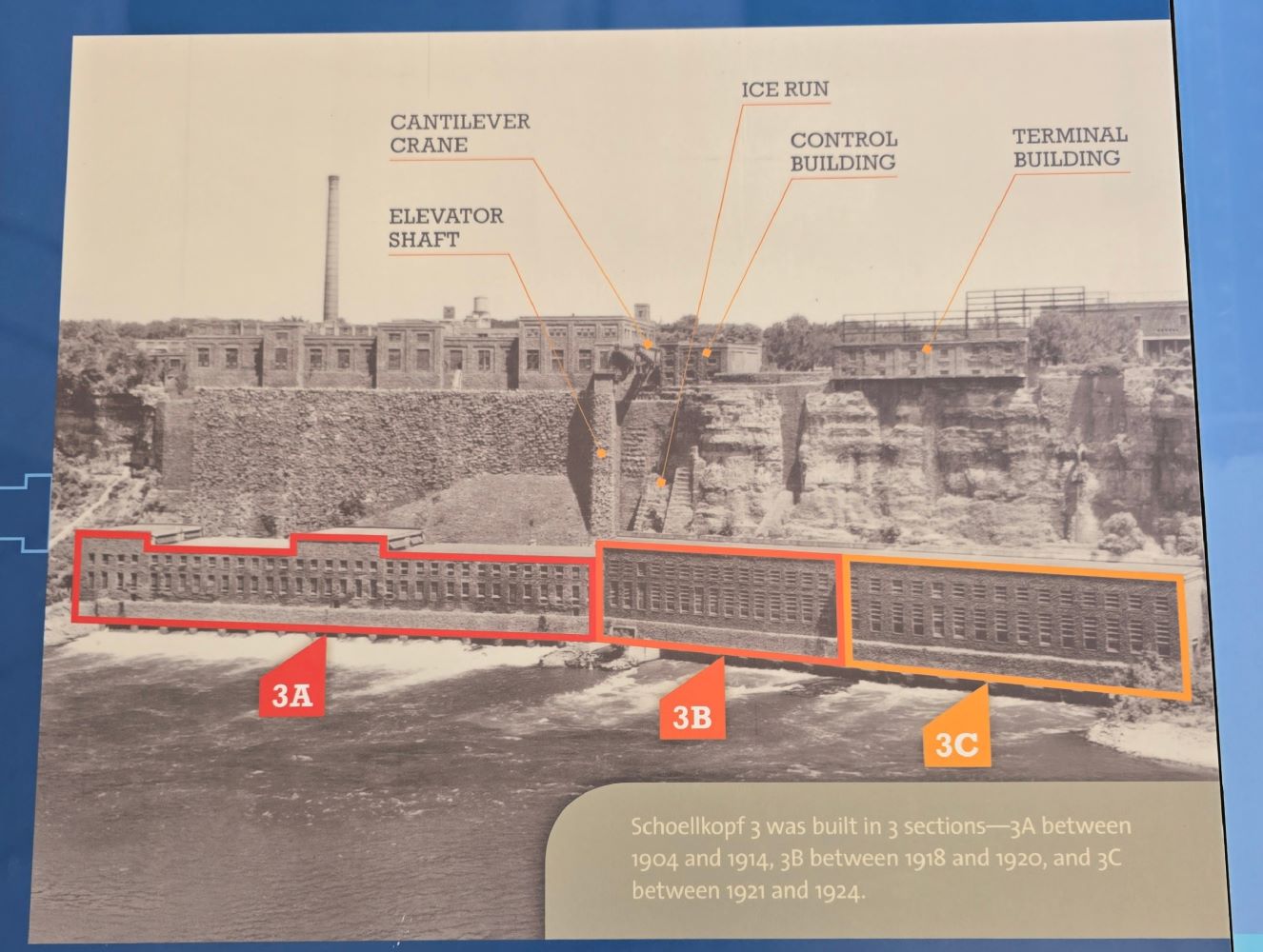

Schoellkopf Power Station No. 3, built in three stages between 1904 and 1924 — the world’s largest hydroelectric plant at the time.

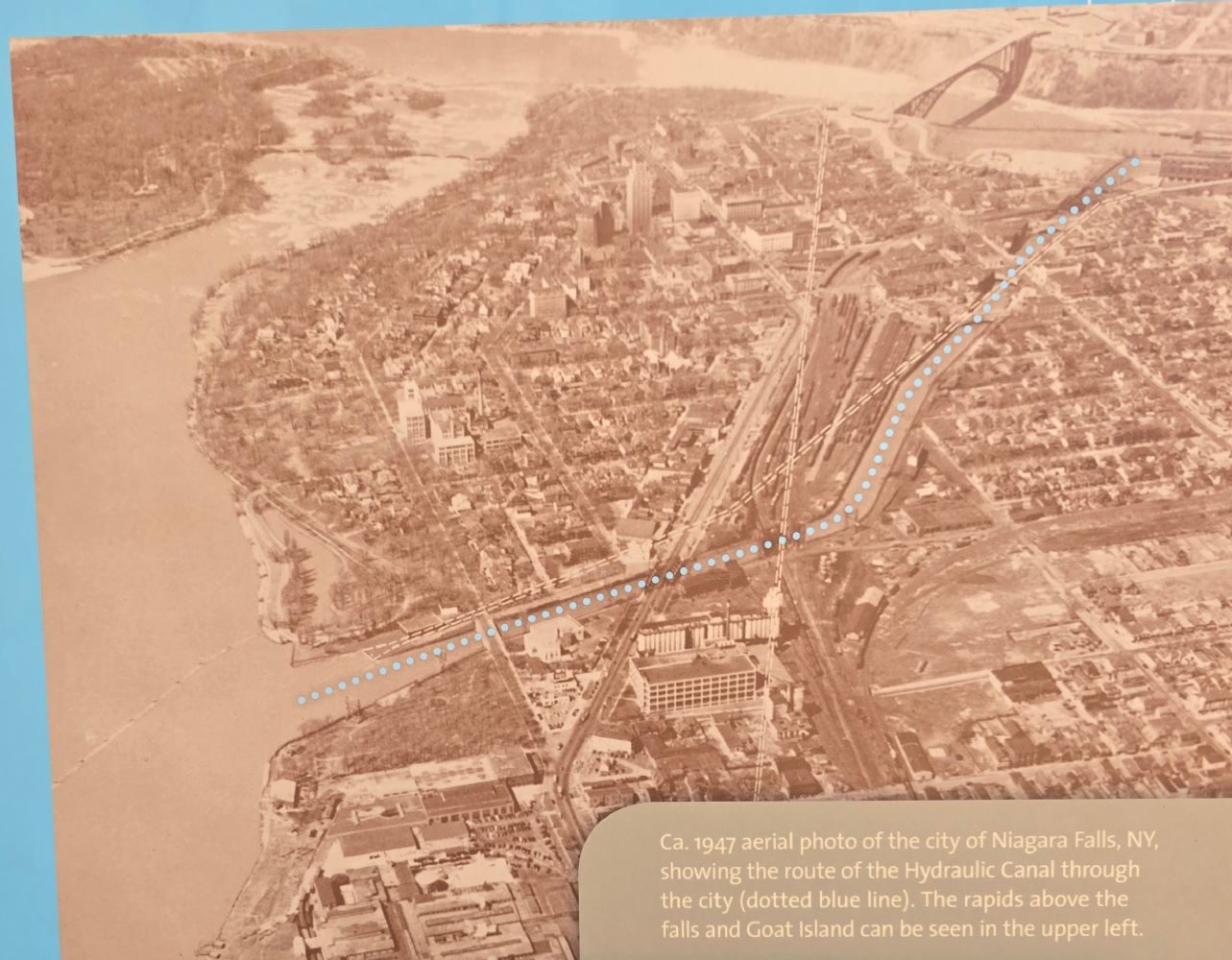

Aerial photo from around 1947, showing the canal that fed water into the turbines.

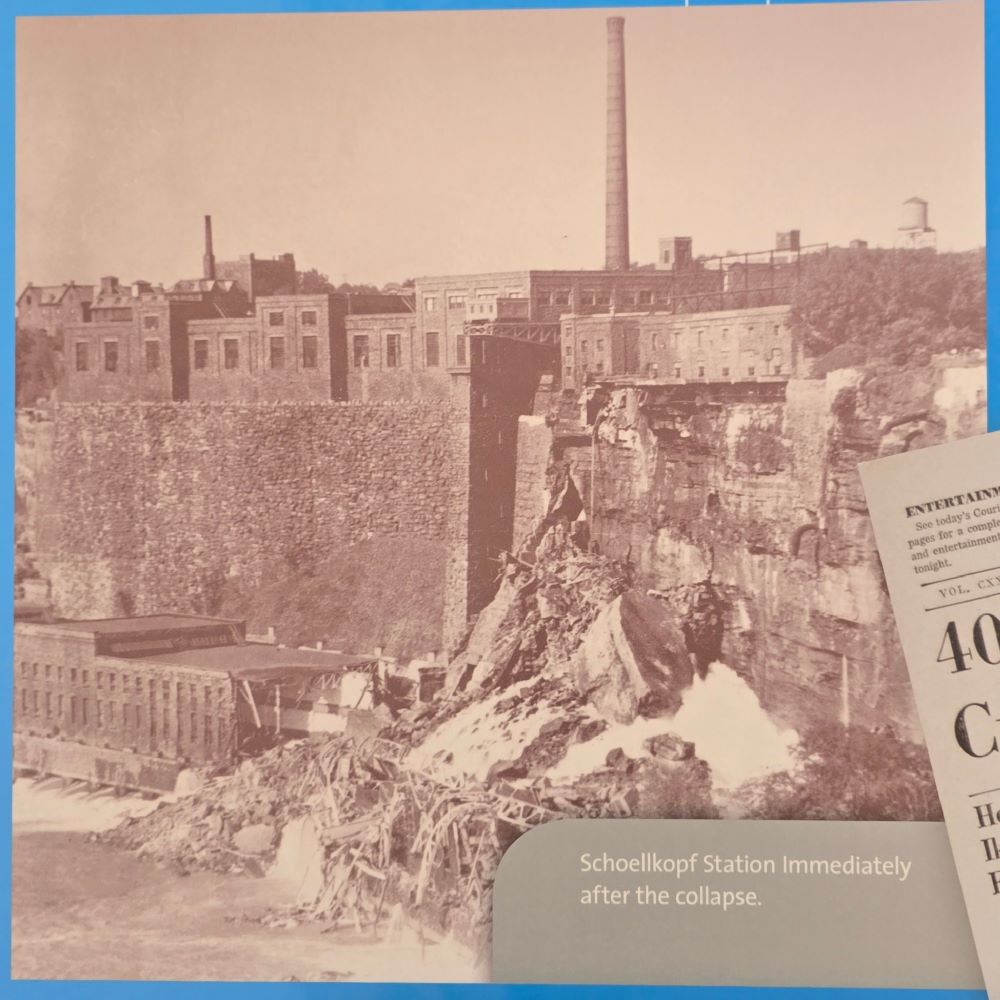

On the morning of June 7, 1956, a small leak was discovered. It quickly worsened into a landslide that destroyed the entire power plant. Most workers escaped, but one was killed.

After the landslide

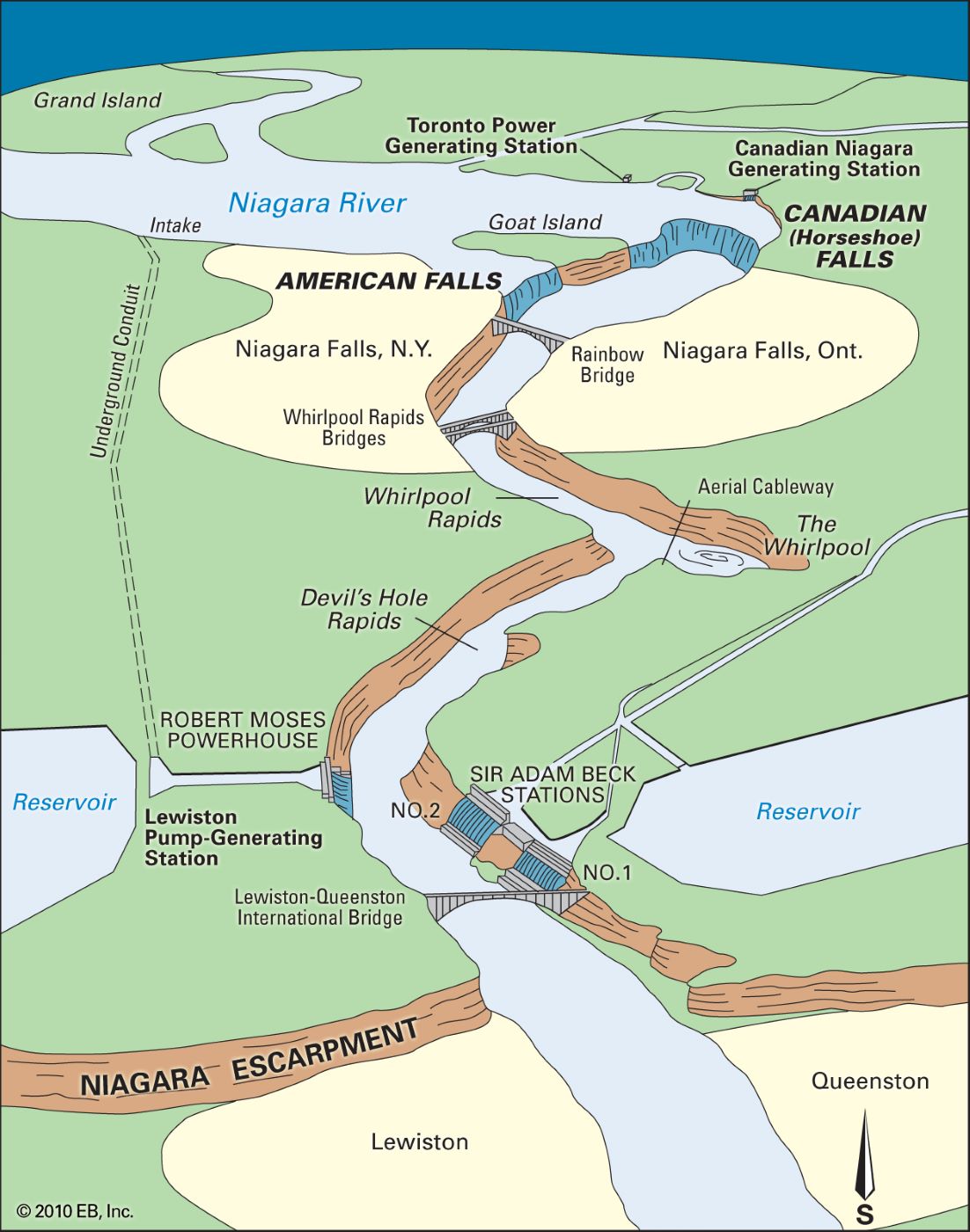

The loss caused an energy shortage, prompting immediate plans for a new power station. After disputes between private companies and New York State, the state took charge. Construction began in 1958, and the new plant went online in 1961.

Diagram from Britannica: the American power plant and reservoir (lower left) and the Canadian plant across the river.

The Niagara River thus serves a “dual purpose”: tourism and power generation. To balance both, the International Control Dam was built — diverting more water for power during off-season (winter all-day and summer nighttime) and more for the falls during peak tourist times. On average, about half of the flow is used for hydroelectricity. Even with this diversion, Niagara Falls still ranks seventh in the world by flow rate — fifth if left unaltered4.

For comparison: the Horseshoe Falls from the Canadian side in winter over a decade ago — can you see the reduced flow? (Taken on an old iPhone 4!)

A Bit of Geology and History

The Niagara Escarpment, seen above, is part of a long ridge formed because the harder dolomite layer on the south resists erosion better than the softer shale to the north. The river’s passage over this cliff created the falls.

Niagara Escarpment

10,000 years ago, the falls were located near today’s power plants. Erosion has moved them 11 km southward. The Horseshoe’s iconic “U” shape developed over the last 300 years. Diverting water for power has slowed this erosion. In the distant future, the falls will retreat into Lake Erie and disappear.

The changing shape of Horseshoe Falls over time

This year, 2025, marks the 140th anniversary of Niagara Falls State Park — America’s first state park, established in 1885 thanks to the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture. Born in Hartford in 1822, Olmsted designed many landmarks: New York’s Central Park, Chicago’s Washington and Jackson Parks, Mount Royal Park in Montreal, and several university campuses — Cornell, Stanford, UC Berkeley, University of Chicago, Yale, and more. No wonder so many campuses share a familiar aesthetic!

Riverside, a Chicago suburb designed by Olmsted — notice the curving roads amidst a grid of straight ones.

And with that, our journey through upstate New York comes to an end. 🌸🎉 (Took me almost four months to finish writing — at last!)

-

Cave of the Winds tickets can only be purchased on-site at Goat Island for a specific entry time. Since we had already experienced the falls up close on the Maid of the Mist — and didn’t want another soaking — we skipped it. ↩︎

-

The nearby Aquarium (Points 12 and 13) requires separate tickets. Since we weren’t traveling with kids this time, we didn’t visit. ↩︎

-

It was scorching at noon — in hindsight, we should’ve taken the shuttle or driven. ↩︎

-

The top three waterfalls by volume are all on the Congo River in Africa. Though less steep, their flow is massive. The Inga Falls ranks first — ten times the flow of Niagara! Its total drop is 96 meters (about twice Niagara’s) spread over 15 km, which makes it debatably a “waterfall.” The Congo River, second only to the Amazon in discharge, has rapids so strong they even separate fish populations, creating remarkable biodiversity. ↩︎